Recognizing white privilege begins with truly understanding the term itself.

It is fair to have proper education. It is unfair that not everyone has it. It is fair to have comfort. It is unfair that not everyone has it. Fearless. - Street Art

Today, white privilege is often described through the lens of Peggy McIntosh’s groundbreaking essay “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” Originally published in 1988, the essay helps readers recognize white privilege by making its effects personal and tangible. For many, white privilege was an invisible force that white people needed to recognize. It was being able to walk into a store and find that the main displays of shampoo and panty hose were catered toward your hair type and skin tone. It was being able to turn on the television and see people of your race widely represented. It was being able to move through life without being racially profiled or unfairly stereotyped. All true.

This idea of white privilege as unseen, unconscious advantages took hold. It became easy for people to interpret McIntosh’s version of white privilege—fairly or not—as mostly a matter of cosmetics and inconvenience.

Those interpretations overshadow the origins of white privilege, as well as its present-day ability to influence systemic decisions. They overshadow the fact that white privilege is both a legacy and a cause of racism. And they overshadow the words of many people of color, who for decades recognized white privilege as the result of conscious acts and refused to separate it from historic inequities.

In short, we’ve forgotten what white privilege really means—which is all of this, all at once. And if we stand behind the belief that recognizing white privilege is integral to the anti-bias work of white educators, we must offer a broader recognition.

A recognition that does not silence the voices of those most affected by white privilege; a recognition that does not ignore where it comes from and why it has staying power.

Racism vs. White Privilege

Having white privilege and recognizing it is not racist. But white privilege exists because of historic, enduring racism and biases. Therefore, defining white privilege also requires finding working definitions of racism and bias.

So, what is racism? One helpful definition comes from Matthew Clair and Jeffrey S. Denis’s “Sociology on Racism.” They define racism as “individual- and group-level processes and structures that are implicated in the reproduction of racial inequality.” Systemic racism happens when these structures or processes are carried out by groups with power, such as governments, businesses or schools. Racism differs from bias, which is a conscious or unconscious prejudice against an individual or group based on their identity.

Basically, racial bias is a belief. Racism is what happens when that belief translates into action. For example, a person might unconsciously or consciously believe that people of color are more likely to commit crime or be dangerous. That’s a bias. A person might become anxious if they perceive a Black person is angry. That stems from a bias. These biases can become racism through a number of actions ranging in severity, and ranging from individual- to group-level responses:

- A person crosses the street to avoid walking next to a group of young Black men.

- A person calls 911 to report the presence of a person of color who is otherwise behaving lawfully.

- A police officer shoots an unarmed person of color because he “feared for his life.”

- A jury finds a person of color guilty of a violent crime despite scant evidence.

- A federal intelligence agency prioritizes investigating Black and Latino activists rather than investigate white supremacist activity.

Both racism and bias rely on what sociologists call racialization. This is the grouping of people based on perceived physical differences, such as skin tone. This arbitrary grouping of people, historically, fueled biases and became a tool for justifying the cruel treatment and discrimination of non-white people. Colonialism, slavery and Jim Crow laws were all sold with junk science and propaganda that claimed people of a certain “race” were fundamentally different from those of another—and they should be treated accordingly. And while not all white people participated directly in this mistreatment, their learned biases and their safety from such treatment led many to commit one of those most powerful actions: silence.

And just like that, the trauma, displacement, cruel treatment and discrimination of people of color, inevitably, gave birth to white privilege.

So, What Is White Privilege?

White privilege is—perhaps most notably in this era of uncivil discourse—a concept that has fallen victim to its own connotations. The two-word term packs a double whammy that inspires pushback. 1) The word white creates discomfort among those who are not used to being defined or described by their race. And 2) the word privilege, especially for poor and rural white people, sounds like a word that doesn’t belong to them—like a word that suggests they have never struggled.

This defensiveness derails the conversation, which means, unfortunately, that defining white privilege must often begin with defining what it’s not. Otherwise, only the choir listens; the people you actually want to reach check out. White privilege is not the suggestion that white people have never struggled. Many white people do not enjoy the privileges that come with relative affluence, such as food security. Many do not experience the privileges that come with access, such as nearby hospitals.

And white privilege is not the assumption that everything a white person has accomplished is unearned; most white people who have reached a high level of success worked extremely hard to get there. Instead, white privilege should be viewed as a built-in advantage, separate from one’s level of income or effort.

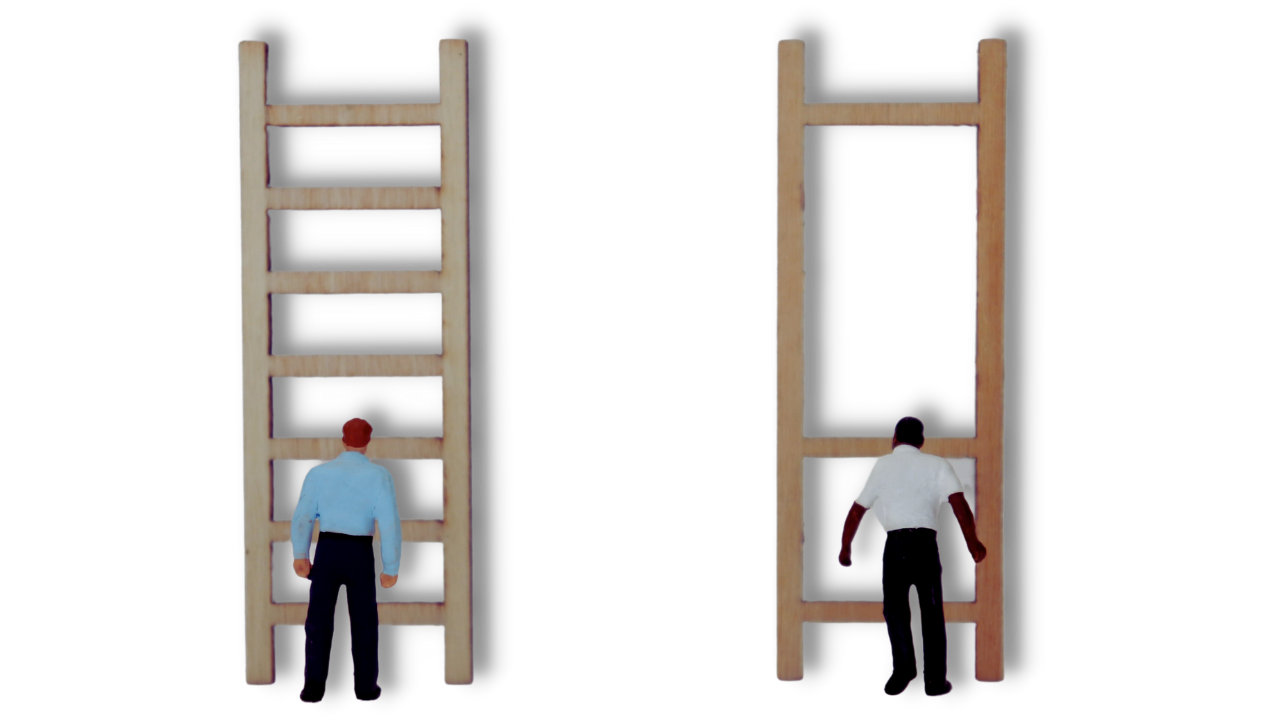

Francis E. Kendall, author of Diversity in the Classroom and Understanding White Privilege: Creating Pathways to Authentic Relationships Across Race, comes close to giving us an encompassing definition: “having greater access to power and resources than people of color [in the same situation] do.” But in order to grasp what this means, it’s also important to consider how the definition of white privilege has changed over time.

White Privilege Through the Years

In a thorough article, education researcher Jacob Bennett tracked the history of the term. Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, “white privilege” was less commonly used but generally referred to legal and systemic advantages given to white people by the United States, such as citizenship, the right to vote or the right to buy a house in the neighborhood of their choice.

It was only after discrimination persisted for years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that people like Peggy McIntosh began to view white privilege as being more psychological—a subconscious prejudice perpetuated by white people’s lack of awareness that they held this power. White privilege could be found in day-to-day transactions and in white people’s ability to move through the professional and personal worlds with relative ease.

But some people of color continued to insist that an element of white privilege included the aftereffects of conscious choices. For example, if white business leaders didn’t hire many people of color, white people had more economic opportunities. Having the ability to maintain that power dynamic, in itself, was a white privilege, and it endures. Legislative bodies, corporate leaders and educators are still disproportionately white and often make conscious choices (laws, hiring practices, discipline procedures) that keep this cycle on repeat.

The more complicated truth: White privilege is both unconsciously enjoyed and consciously perpetuated. It is both on the surface and deeply embedded into American life. It is a weightless knapsack—and a weapon.

It depends on who’s carrying it.

White Privilege as the “Power of Normal”

Sometimes the examples used to make white privilege visible to those who have it are also the examples least damaging to people who lack it. But that does not mean these examples do not matter or that they do no damage at all.

These subtle versions of white privilege are often used as a comfortable, easy entry point for people who might push back against the concept. That is why they remain so popular. These are simple, everyday things, conveniences white people aren’t forced to think about.

These often-used examples include:

- The first-aid kit having “flesh-colored” Band-Aids that only match the skin tone of white people.

- The products white people need for their hair being in the aisle labeled “hair care” rather than in a smaller, separate section of “ethnic hair products.”

- The grocery store stocking a variety of food options that reflect the cultural traditions of most white people.

But the root of these problems is often ignored. These types of examples can be dismissed by white people who might say, “My hair is curly and requires special product,” or “My family is from Poland, and it’s hard to find traditional Polish food at the grocery store.”

This may be true. But the reason even these simple white privileges need to be recognized is that the damage goes beyond the inconvenience of shopping for goods and services. These privileges are symbolic of what we might call “the power of normal.” If public spaces and goods seem catered to one race and segregate the needs of people of other races into special sections, that indicates something beneath the surface.

White people become more likely to move through the world with an expectation that their needs be readily met. People of color move through the world knowing their needs are on the margins. Recognizing this means recognizing where gaps exist.

White Privilege as the “Power of the Benefit of the Doubt”

The “power of normal” goes beyond the local CVS. White people are also more likely to see positive portrayals of people who look like them on the news, on TV shows and in movies. They are more likely to be treated as individuals, rather than as representatives of (or exceptions to) a stereotyped racial identity. In other words, they are more often humanized and granted the benefit of the doubt. They are more likely to receive compassion, to be granted individual potential, to survive mistakes.

This has negative effects for people of color, who, without this privilege, face the consequences of racial profiling, stereotypes and lack of compassion for their struggles.

In these scenarios, white privilege includes the facts that:

- White people are less likely to be followed, interrogated or searched by law enforcement because they look “suspicious.”

- White people’s skin tone will not be a reason people hesitate to trust their credit or financial responsibility.

- If white people are accused of a crime, they are less likely to be presumed guilty, less likely to be sentenced to death and more likely to be portrayed in a fair, nuanced manner by media outlets (see the #IfTheyGunnedMeDown campaign).

- The personal faults or missteps of white people will likely not be used to later deny opportunities or compassion to people who share their racial identity.

This privilege is invisible to many white people because it seems reasonable that a person should be extended compassion as they move through the world. It seems logical that a person should have the chance to prove themselves individually before they are judged. It’s supposedly an American ideal.

But it’s a privilege often not granted to people of color—with dire consequences.

For example, programs like New York City’s now-abandoned “Stop and Frisk” policy target a disproportionate number of Black and Latinx people. People of color are more likely to be arrested for drug offenses despite using at a similar rate to white people. Some people do not survive these stereotypes. In 2017, people of color who were unarmed and not attacking anyone were more likely to be killed by police.

Those who survive instances of racial profiling—be they subtle or violent—do not escape unaffected. They often suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, and this trauma in turn affects their friends, families and immediate communities, who are exposed to their own vulnerability as a result.

A study conducted in Australia (which has its own hard history of subjugating Black and Indigenous people) perfectly illustrates how white privilege can manifest in day-to-day interactions—daily reminders that one is not worthy of the same benefit of the doubt given to another. In the experiment, people of different racial and ethnic identities tried to board public buses, telling the driver they didn’t have enough money to pay for the ride. Researchers documented more than 1,500 attempts. The results: 72 percent of white people were allowed to stay on the bus. Only 36 percent of Black people were extended the same kindness.

Just as people of color did nothing to deserve this unequal treatment, white people did not “earn” disproportionate access to compassion and fairness. They receive it as the byproduct of systemic racism and bias.

And even if they are not aware of it in their daily lives as they walk along the streets, this privilege is the result of conscious choices made long ago and choices still being made today.

White Privilege as the “Power of Accumulated Power”

Perhaps the most important lesson about white privilege is the one that’s taught the least.

The “power of normal” and the “power of the benefit of the doubt” are not just subconscious byproducts of past discrimination. They are the purposeful results of racism—an ouroboros of sorts—that allow for the constant re-creation of inequality.

These powers would not exist if systemic racism hadn’t come first. And systemic racism cannot endure unless those powers still hold sway.

You can imagine it as something of a whiteness water cycle, wherein racism is the rain. That rain populates the earth, giving some areas more access to life and resources than others. The evaporation is white privilege—an invisible phenomenon that is both a result of the rain and the reason it keeps going.

McIntosh asked herself an important question that inspired her famous essay, “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”: “On a daily basis, what do I have that I didn’t earn?” Our work should include asking the two looming follow-up questions: Who built that system? Who keeps it going?

The answers to those questions could fill several books. But they produce examples of white privilege that you won’t find in many broad explainer pieces.

For example, the ability to accumulate wealth has long been a white privilege—a privilege created by overt, systemic racism in both the public and private sectors. In 2014, the Pew Research Center released a report that revealed the median net worth of a white household was $141,900; for Black and Hispanic households, that dropped to $11,000 and $13,700, respectively. The gap is huge, and the great “equalizers” don’t narrow it. Research from Brandeis University and Demos found that the racial wealth gap is not closed when people of color attend college (the median white person who went to college has 7.2 times more wealth than the median Black person who went to college, and 3.9 times more than the median Latino person who went to college). Nor do they close the gap when they work full time, or when they spend less and save more.

The gap, instead, relies largely on inheritance—wealth passed from one generation to the next. And that wealth often comes in the form of inherited homes with value. When white families are able to accumulate wealth because of their earning power or home value, they are more likely to support their children into early adulthood, helping with expenses such as college education, first cars and first homes. The cycle continues.

This is a privilege denied to many families of color, a denial that started with the work of public leaders and property managers. After World War II, when the G.I. Bill provided white veterans with “a magic carpet to the middle class,” racist zoning laws segregated towns and cities with sizable populations of people of color—from Baltimore to Birmingham, from New York to St. Louis, from Louisville to Oklahoma City, to Chicago, to Austin, and in cities beyond and in between.

These exclusionary zoning practices evolved from city ordinances to redlining by the Federal Housing Administration (which wouldn’t back loans to Black people or those who lived close to Black people), to more insidious techniques written into building codes. The result: People of color weren’t allowed to raise their children and invest their money in neighborhoods with “high home values.” The cycle continues today. Before the 2008 crash, people of color were disproportionately targeted for subprime mortgages. And neighborhood diversity continues to correlate with low property values across the United States. According to the Century Foundation, one-fourth of Black Americans living in poverty live in high-poverty neighborhoods; only 1 in 13 impoverished white Americans lives in a high-poverty neighborhood.

The inequities compound. To this day, more than 80 percent of poor Black students attend a high-poverty school, where suspension rates are often higher and resources often more limited. Once out of school, obstacles remain. Economic forgiveness and trust still has racial divides. In a University of Wisconsin study, 17 percent of white job applicants with a criminal history got a call back from an employer; only five percent of Black applicants with a criminal history got call backs. And according to the National Bureau of Economic Research, Black Americans are 105 percent more likely than white people to receive a high-cost mortgage, with Latino Americans 78 percent more likely. This is after controlling for variables such as credit score and debt-to-income ratios.

Why mention these issues in an article defining white privilege? Because the past and present context of wealth inequality serves as a perfect example of white privilege.

If privilege, from the Latin roots of the term, refers to laws that have an impact on individuals, then what is more effective than a history of laws that explicitly targeted racial minorities to keep them out of neighborhoods and deny them access to wealth and services?

If white privilege is “having greater access to power and resources than people of color [in the same situation] do,” then what is more exemplary than the access to wealth, the access to neighborhoods and the access to the power to segregate cities, deny loans and perpetuate these systems?

This example of white privilege also illustrates how systemic inequities trickle down to less harmful versions of white privilege. Wealth inequity contributes to the “power of the benefit of the doubt” every time a white person is given a lower mortgage rate than a person of color with the same credit credentials. Wealth inequity reinforces the “power of normal” every time businesses assume their most profitable consumer base is the white base and adjust their products accordingly.

And this example of white privilege serves an important purpose: It re-centers the power of conscious choices in the conversation about what white privilege is.

People can be ignorant about these inequities, of course. According to the Pew Research Center, only 46 percent of white people say that they benefit “a great deal” or “a fair amount” from advantages that society does not offer to Black people. But conscious choices were and are made to uphold these privileges. And this goes beyond loan officers and lawmakers. Multiple surveys have shown that many white people support the idea of racial equality but are less supportive of policies that could make it more possible, such as reparations, affirmative action or law enforcement reform.

In that way, white privilege is not just the power to find what you need in a convenience store or to move through the world without your race defining your interactions. It’s not just the subconscious comfort of seeing a world that serves you as normal. It’s also the power to remain silent in the face of racial inequity. It’s the power to weigh the need for protest or confrontation against the discomfort or inconvenience of speaking up. It’s getting to choose when and where you want to take a stand. It’s knowing that you and your humanity are safe.

And what a privilege that is.

So, what can I do once I recognize my white privilege?

Beyond recognition, white people can use their white privilege in a way that is beneficial to all people. Here’s how.*

Don’t take it personally or use discomfort as an excuse to disengage.

Feelings of guilt or defensiveness are common responses, but ultimately, they’re counterproductive. Rather than centering your own feelings of discomfort, center the feelings of people of color in evaluating what to do with this information. If your instinct is telling you it’s more comfortable to retreat or reassure yourself that you are not racist, think instead, What actions can I take to help?

Learn when to listen, when to amplify and when to speak up.

When people of color speak to their experiences of oppression, it’s important for white people not to dominate the conversation or question those experiences. You can use your privilege to amplify those voices. Share the work and perspectives of people of color on social media. Credit colleagues of color for ideas. This not only helps marginalized people reach that audience but also helps spread their message from the source, rather than through the lens of a white person.

That said, there are also times when white people should speak up. It’s not fair to burden people of color by making them always take the lead on anti-bias work or intervening when something offensive is said or done. If you hear racist remarks, speak up. If you see opportunities to educate fellow white people about race, do so. As an ally, your privilege can be a tool to reach people who may be more likely to listen to you or relate to your journey in understanding your own relationship to race and white privilege.

Educate yourself.

Just as you should not always expect people of color to take the lead on speaking out against racism, you also shouldn’t expect them to educate you on racism. While it’s OK to ask questions of those who have expressed a willingness to answer them, you have the power to educate yourself. Seek out books and articles on the topic written by people of color. Critically evaluate documentaries that surround topics like slavery, race, the U.S. prison system and more. We have more access to information created by people of color than ever before. Take advantage of it, and avoid burdening friends or coworkers of color with constant questions about their experiences.

Educate fellow white people.

Share what you’ve learned. Push through discomfort and demand courageous conversations in your circles. Do not let peers get away with problematic remarks without making a serious effort to engage them.

Risk your unearned benefits to benefit others.

You have most likely seen a viral video featuring Joy DeGruy talking about her biracial sister-in-law using her white skin privilege to question why Joy was receiving undue scrutiny from a cashier. She risks her comfort and her easy transactions with the store to point out this unfairness and ultimately receives support from witnesses and management.

There are other ways to do this in our daily lives. It can be as simple as intervening if you see a boss or fellow educator treating someone differently because of their racial identity. It can mean advocating for a coworker to receive equal pay or opportunities. It can mean being an active witness when you see people of color confronted by law enforcement or harassed by bigots and letting them know you are there to support them and record the interaction if necessary. And it most certainly can mean engaging directly in anti-bias work, such as instilling more inclusive practices at your school or business or working with people committed to allyship and anti-racist activism, such as SURJ.

*Some of these steps were adapted from suggestions in Emily Chiariello’s “Why Talk About Whiteness?”